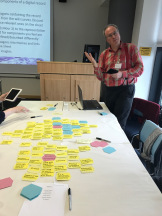

The 27 participants were organized in five groups, each carefully chosen to reflect their geographic and disciplinary diversity. The group I was part of identified what we perceived as initial stumbling blocks – definitions of record, and definitions of evidence. As we began to organize the elements or components that had arisen through the previous crowd-sourcing activities, certain themes emerged: items we considered part of a set of necessary and sufficient components for a digital record that could be trusted as evidence if needed; activities necessary as part of records management; and ancillary issues identifying contexts.

We approached the exercise from the perspective of ‘records’ (I leave a precise definition to the reader). The problem of course with digital material is that records and documents as understood by archivists and records managers are but a small fraction of digital content being managed as an information or business asset. This is part of the narrative of exploding digital content – there is too much information – how can we manage it? What must we manage? And how will technology help us?

So I was very interested to read a blog post by Mike Caulfield entitled ‘Information Underload’ in which he proposes that the problem is not too much information but too little information of value. What we used to say about databases, ‘garbage in, garbage out’, can now be said about big data. The companies that get this – and are fixing the problem – are not relying on analytics to manage or interpret the data they have, but are fixing the problem with the data to begin with. (Caulfield offers Netflix as an example – their analytics served up content that no one wanted, so they created better content.)

All this makes research like RecordDNA, and InterPARES Trust, all the more critical. Previous InterPARES research has found that the ability to preserve digital records begins at the time of their creation and depends on a chain of preservation. RecordDNA is looking at digital objects of all types. If we can identify what we need from our digital records (data, and other digital objects), then we can preserve a trustworthy evidence base.